This is a cross-post from our internal engineering blog, sketching out a baseline set of advice for engineering team operations at Helsing. We believe it is essential to reduce meeting overhead, use asynchronous communication where possible, and generally recover time to focus on “getting shit done”. We figured this article might be useful to engineering leaders outside Helsing and thus chose to publish the article on our public blog.

At Helsing, we encourage teams to find their own way of operating that suits the work they do: how long sprints are, how business goals get broken down into engineering problems, what process and rituals are used, and how to communicate and coordinate between teams. We require a few key processes, aiming to balance between process-overhead and company-wide alignment. These are:

- Quarterly OKRs — to encourage teams to take a moment and check they’re running a direction aligned with company goals

- Monthly team updates — to break down quarterly goals into more concrete units of progress and support longer-burn alignment across teams

- Weekly demos — to share progress, ideas, and build a sense of community!

We encourage this flexibility because we believe it is both part of having ownership over the outcomes a team is a responsible for, but also because different teams are working on varied problems, at different stages of the research, development, delivery, and operations cycle. As such, there is not really a one size fits all approach to team operations and planning.

That said, this flexibility shouldn’t result in lack of advice as to how one might operate a team and what pitfalls can be avoided. So, here we lay out how many successful teams have operated and explain a little bit about why these systems work and how all the parts connect.

The hope is that, wherever you are on the spectrum, minimal tweaks can be made to adapt such a model to work for your work and your teams.

The goal, in the end, is to help teams operate efficiently, so they can focus on executing effectively. Being able to scale up, while maintaining highly independent and execution focused teams is a huge boon to any company. To do that, you have to operate in a mode that reinforces improvement over time while also reducing overhead.

Before diving in, two assumptions are baked into this:

- Your team is small . A small team has 8 or fewer people. This is important — with small teams everyone on the team can, and should, know what each and every other person on the team is owning and the rough status of those items. This allows us to vastly simplify the complexity of meetings.

- Your team has context. Not only do people need to know what each other is working on, but they need to understand team priorities, why what you’re building matters, what you’re committed to, and ultimately how it all fits together. If you’re on a team and you don’t know this — demand it. If you’re a team lead and you hear people asking for this — help them. This context is essential: it makes planning easy by reducing it to what the best course of action is to achieve the shared outcomes rather than wasting time inefficiently dumping context in single meetings.

- Your team is in contact. At Helsing we achieve this by being mostly co-located and taking advantage of the serendipitous information sharing and conversations that arise from that. For predominantly- or fully-remote teams you’ll likely need to add in a little structure to ensure this continues.

At its heart…

People own outcomes and deliverables, not tasks.

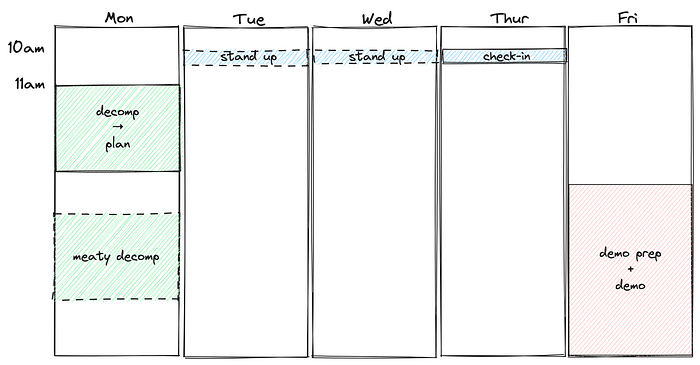

The calendar…

weekly calendar (dotted = optional)

Sessions

- [30–60m] Weekly decomp

- [15m] Weekly check-in

- [30m] Monthly plan + retros

- [60–90m — agenda driven] Meaty Decomp

Comms

- Weekly plans

- Monthly updates

- Quarterly OKRs

Principles

Four high level decisions are important to lay out that impact the other decisions below.

🖥 Bias towards asynchronous (over-) communication

This means all meetings must have notes , and those notes should be distributed broadly. This allows you to minimise meeting attendance, improve ownership, and maximise the flow of work.

- Send regular status updates of what the team is working on.

- Use actual meeting time for things that require synchronous communication: ideation, problem solving, deeper alignment.

- An explicit goal for most meetings should be to minimise attendance to only the required attendees.

- Very few internal meetings require the entire team to attend, usually 2–3 will do for any given topic

- Meetings with other teams rarely require more than 1 team representative

💯 Deliver weekly

It’s easier to estimate what is feasible to deliver in a week. As the time horizon creeps beyond that the complexity of work ticks up significantly, making estimates much harder. Equally, once you’re at 2+ weeks, people always tend towards overestimate because they think of it as 10 days and don’t account for missed days, demos, interviewing, other meetings. Across a 10-day window so much can happen.

👟 Plan for 4 days, not 5

Across the team you’ll have folks doing interviews, preparing for the weekly demo, getting pulled into ad-hoc discussions, taking a half day off, etc. If they don’t end up doing that, great, you have 25% extra time to help with other things and make additional improvements!

📁 Use planning documents for planning

Trite, but when teams complain about planning being onerous and not useful, they are almost always teams that don’t actually use their planning docs (OKRs, monthly updates, weekly plans). This is their own fault. Planning documents, while also a communication to the org, must be useful for the team authoring them. Team should use OKRs to inform Monthly plans, and those to inform weekly goals. And vice-versa: weekly work updates monthly plans, informs future OKRs. OKRs should be top of mind in our Monthly planning, and those plans top of mind in the weekly decomp. If your planning documents aren’t useful, throw them out and start over.

Finally, let’s take a look at the weekly meeting agenda in detail, one meeting at a time.

Decomp & Planning

If a team has good context and alignment on long and mid-term priorities, it’s very likely that any one member of the team can determine and articulate the immediate priorities for the team at large. This then leads to most members being able to independently prioritise what work they need to achieve the outcomes they are responsible for. Time together should then be dedicated to ensuring we’ve correctly understood how to execute and coordinate those next steps as a team.

Most planning sessions I’ve experienced fail at this — whether this is a backlog/Kanban style review, or a more execution + goals-oriented tasking. Many planning meetings devolve into task assignment and don’t make use of the limited synchronous time the team has to align on how the work is going to get done.

This results in several, if not many, ad-hoc, usually 1:1, meetings to do this decomp. This leads to more,

- meeting overhead [sad]

- information siloing [unless you’re really strict with meeting notes]

Spending your planning time focused on decomp exposes more of the team to more technical context and also does a much better job of raising potential planning complexities and uncertainties than any form of task assignment.

Operationally…

This meeting should be focused on aligning on concrete outcomes for the week.__ What challenges are the team facing, what commitments do we have, and what are we each individually, and together, doing about them. A useful fallback question to drive this discussion can be What are we going to demo at the end of the week?

Time should be spent querying whether things are the right things to do: are they the most important thing and are they the right thing? The name here is important. This is synchronous time together and should be treated as such: push asynchronous activities out of this synchronous space. Eg, folks should review backlogs as pre work to such sessions. Creation and assigning of tickets should be taken as follow ups by the team members. Don’t hold everyone hostage!

You’ll also notice that task assignment is more or less implicit or automatic after the team has discussed the engineering challenges in depth: those individuals who are most informed/engaged/interested in the engineering discussion are likely also those most suitable for working on those topics.

When topics seem to be getting really in the weeds and it seems a deeper discussion is needed, flag them to be addressed in the Meaty Decomp later that day.

This meeting should take place at ~11am . Lots of planning starts at 9am on Monday, but realistically lots of people won’t have had time to spool their mental cache back up, process any email backlog, and get their brains generally in order. 11am is a good time to allow people to have found their feet, had a coffee, and confront their thoughts on the challenges ahead. The lost hours lose out against the effectiveness gains.

This meeting results in a concrete plan __ — a set of outcomes, with owners, that are going to be delivered this week. That plan should be communicated to as broad an audience as possible. Doing so allows misalignment from outside the team to be surfaced early, or for beneficial coordination to be taken advantage of.

Don’t use this meeting for retros __(but equally don’t shut down discussion of improvement points) — there are rarely insightful points that come out of a single sprint’s worth of learnings. Prompting for a retro here (or every week) explicitly will be a waste of time. (See separate discussion on monthly retros below.)

Plan for 4 days . I’ve laid the reasoning for this above. In an ideal world of perfect prediction, this just means you get 20% time to work on other important tasks and respond to inbound requests. Great. Otherwise, it makes your work far more predictable.

Finally, to the team leads out there: you need to make the assessment of what outcome is in the intersection of most important, most urgent, and most at risk. It is your job as a team lead to present, contextualise, and if necessary defend (weakly held!) the focus themes for the week. This usually requires preparation (eg, 9am-11am ;)), and this is also where you should be allocating your time to support implementation and delivery directly — contributing code, prioritising CR, helping review proposals, pair-programming.

Meaty Decomp

This is the most unusual meeting — very few guides to running teams recommend such a session. When it does exist, you may see it called called “Tech discussion”, or similar, but the name here is important. At Helsing, we’re strong believers in nominative determinism when it comes to anything: email lists, slack rooms, meetings, etc. The goal of this meeting is to spend time focused on decomposing and analysing the deeper tech challenges the team is facing: not planning, not free wheeling discussion, but problem decomp.

By providing a dedicated space to get together and dive deeper into a problem space, we seek several benefits and to avoid several pitfalls:

- Reduce ad-hoc meeting overhead as well as information siloing (as above)

- Ensure that only interested + relevant people are required to attend

- Create context and alignment on technical decisions in the team (Decomp sessions should regularly produce ADRs for the team)

We also provide a forum

- To pull in other experts + teams early on in technical discussions

- For folks to flag issues they need help breaking down

- For learning and collaborating on technical problem solving at a level higher than pair programming

Many teams I’ve experienced lack such a space, and their technical decision making suffers both in terms of individual quality and collective coherence. Equally, teams without this space tend to have much less context on how decisions on their team are made in context of the broader technical environment in which they operate.

Operationally..

This is an “Agenda Driven Meeting” (ADM). ADMs are meetings that are in the calendar but attendees only attend if there is something on the agenda to discuss. If there are no items on the Agenda, the meeting owner cancels the meeting 30m before it is due to start.

This meeting tends to have topics injected for one of two reasons

- Complex technical discussions that would eat into all the weekly decomp . Lots of singular technical topics don’t require the whole team to be present. Similarly, you may want input from folks outside of the team, so as these come up in the weekly Decomp & Planning, flag them to be added to the Meaty Decomp session.

- Longer burn decision making . Sometimes we know we have a “one way door” decision to make — something that once we commit one way or the other it’ll be extremely costly to walk it back. As we see these, we can add them to the Meaty Decomp so we have time to mull them over, plan, and understand our trade-offs before they’re on the critical path.

Finally, the Agenda for this meeting should be public. This means other teams can see what topics are coming up and you can see theres. Again — we’re biasing towards asynchronous communication and trying to increase shared state.

Thursday check-in

Estimation is hard and therefore all planning is inherently prone to change. As a result, team members need to stay in sync on the progress of not just their tasks, but their teammates’ too, so they can readjust their estimates and plans.

There are many ways of achieving this: daily stand ups, bi-weekly check-ins, daily email updates, Jira ticket status updates, Kanban boards; the list goes on.

Outside of technical implementation, these differ mostly in their weighting of synchronous vs asynchronous communication load.

While we bias towards asynchronous communication, it is useful to have a backstop to for synchronisation. A short check-in before the week comes to a close, where planning uncertainty for the team has resolved, allows the team to quickly readjust their focus, and focus down on closing our remaining items.

It is important to do this synchronously because this can mean some team-members end up helping out with in-flight work, or picking up new tasks, and synchronous time allows them to get up to speed and be effective as fast as possible.

Operationally…

Once you’ve got alignment on what you need to get done each week daily stand ups are not as useful for alignment. Again, set the expectation with team members that they’re responsible for communicating asynchronously about their progress (anything from slack messages, Jira comments, through code review comments — whatever tools you use).

The Check-in meeting serves two purposes, both targeted at ameliorating the fact that even at 4 days, estimation is hard.

- Align on remaining work to hit goals. As with all estimation, some things will be quicker, some slower. So, those that have finished early can, where possible, spend cycles helping others. Team leads can also use this to re-priorities their focus.

- Act as a backstop against people not communicating blockers/dropped goals. When we set the expectation that people doing things asynchronously, that is a good thing — but it’s always worth having a backstop. This meeting allows people who have maybe got stuck in the weeds or bounced across many teams trying to unpick a gnarly thread, to flag as such and get support if they haven’t already. This means it’s also a good place for team leads to pick up on where team members may need help with biasing towards over communication.

No team meetings on Friday

Making any big decisions on a Friday is almost always a mistake. One, they come unstuck over the weekend anyway, and two, people are distracted finishing things off.

Don’t schedule team meetings for Friday. To address specific meetings that you may be convinced you want:

- Friday stand-up — you’re either done or you’re not by this point. You had the Thursday meeting, that should be enough. We’re not in the habit of micromanaging!

- Retro: weekly retros aren’t sufficiently useful to justify a dedicated meeting that interrupts the “crunch window” approaching demos or interrupts people using their extra day productively experimenting!

Having the calendar free enables folks to allocate time to polishing their demo, other activities (like interviewing), or exploring new ideas.

Anyway, we planned for 4 days, right?!

Monthly retro + planning

If the Weekly meeting is “what challenges are in the direction we’re marching?”, the monthly meeting is “Is the direction we’re marching actually the right one for our overall priorities” (eg, OKRs) and (more meta) “Is our way of working still aligned with our goals”?

This meeting should be anchored on OKRs: reviewing our progress. In reviewing progress, retrospect.

- You’ve had 4 weeks — you probably have some observations about what’s been going well and not.

- Retrospecting in the context of what you’re trying to achieve is almost always more effective than “what could have gone better this sprint?”

- Reflect on how you work together as a team and whether there is avoidable friction or frustration.

Come up with the next set of concrete next steps, or adjustments, to your priorities.

Monthly updates

Publish the backward-looking progress and forward-looking plan. This doesn’t need to be complex: focus on what progress was made, what slipped, and what you’re focusing on next.

I’d encourage some embellishment here: this is your chance to explain some context about what’s been delivered and why you prioritised it. This may be obvious to you, but it’s probably not to the rest of your org, and in writing it down you also get to self-rubber-duck.

On stand-ups

Stand-ups have become ubiquitous, but their utility is questionable.

To be clear, stands up are extremely valuable when there are at least one of these problems:

- Lots of moving pieces to coordinate

- Rapidly (think 12–24h) changing state

- Extremely tight near-term deadline (think <= 2 weeks)

If you have those problems, use Stand-ups.

But, if you do have those problems it’s even more important that people bias towards over-communication on asynchronous media. If time is of the essence don’t wait for Stand-ups. And, this is the rub, Daily Stand-ups in the famous yesterday-today-blockers style pushes people towards a daily rhythm. When things are complex, changing, and time-sensitive that can be anathema to success. So, when you have one of the three problems above, think about what cadence you need, make it clear that Stand-ups are a backstop, and focus those Stand-ups only on the problem, not just status reports.

On 1:1s

Consider using Wednesdays for 1:1s. Do these in the morning or later in the day, not in the middle to avoid interrupting flow; see, eg, the Maker’s Schedule.

Conclusion

If you’re starting a new team, or looking to revisit how you operate existing teams, we invite you to consider our best practices!

Maybe even more importantly, we arrived at this by thinking about the problems we were facing and what we needed our teams to achieve and optimised for that. The most important thing is to not just cargo cult existing team operations and instead be intentional about where you spend your most important resource — time.

Author: Sam Rogerson is the VP Engineering at Helsing.