Marcel Gordon has recently joined Helsing as VP Product. Before Helsing, Marcel spent ten years building products at Google and most recently built the Product function at Shift Technology. In this blog post, Marcel shares his thoughts on navigating from problem to solution (and back!).

Helsing is growing very quickly, and we’re rapidly building up a product development organisation (Product + Engineering + AI Researchers). It is critical for us to align on how product development should work; and since we’re taking the time to write it down, we thought we’d share some ideas here as well.

Let’s take a look at some different approaches to defining a product that could be taken by a Product Manager. In each of them, you start by spending time with the customer (if not, go directly to jail, do not pass go). Then:

- The customer identifies some features that they have long wanted added to a key solution that they use every day. You document the feature requirements and provide them to Engineering.

- You dig in with the customer to identify the objective that the “missing features” are meant to address. Once the problem is captured as an objective, you develop a solution with Engineering.

- You go deep with the customer on their business and the levers involved, including Engineering in the discussion. Together, you frame the problem and the possible solutions.

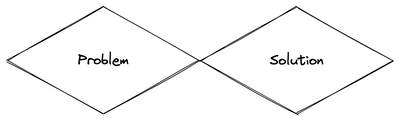

Some of you have probably already observed that we’re moving along the problem / solution axis. It is often represented as shown below, to highlight the divergence and convergence involved both in identifying the right problem to tackle, and in identifying the right solution to the problem. We explore the problem space, nail down a problem to solve, explore the solution space, implement a solution.

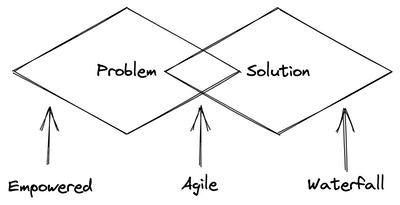

In reality, the problem and the solution are not independent. To give the extreme case, there is no point in focusing a team on solving an unsolvable problem. More generally, we want technical know-how to influence our choice and definition of problem (staying within the set of highly impactful problems). So we can tweak the diagram slightly, and add the three scenarios discussed above based on when we include Engineering in the process (mapping left as an exercise for the reader).

None of these is strictly wrong. However, they carry different risks, costs and challenges on one hand, and pay-offs on another:

- Waterfall: We have clear requirements for Engineering that have been developed quickly and validated with the customer. The customer will be happy in the short term, and Engineering knows what to do. However, there is little scope to trade-off technical complexity against product value, or to understand and build for the bigger picture.

- Agile: We give the Product Manager clear ownership of identifying the problem, but leave space for Product and Engineering to iterate on the nature of the solution together. We can iterate quickly on an existing product, but it is difficult to challenge the fundamental choices involved.

- Empowered: We need an Engineering team willing and capable of engaging with the customer’s problems, not just the technical solutions. We also need a Product Manager capable of driving collaboration and convergence. We will certainly take longer to get to implementation, but we have all the degrees of freedom to discover and build the most impactful product.

We can think about these three approaches as different interfaces between Product and Engineering:

- Waterfall: Input is product requirements; output is code that satisfies all the product requirements. As an Engineer, my job is clear, but I sometimes wonder why we’re doing what we’re doing.

- Agile: Input is a problem (ideally a metric and target); output is a solution that achieves the target. As an Engineer, I’m solving a higher level problem, which is harder and less predictable. [Note: This is good Agile; in bad Agile the input is a list of features, making it Waterfall with sprints.]

- Empowered: Input is a customer; output is customer value. As an Engineer, I have to understand the business, and I’m out of my comfort zone. I spend less time building things, but I understand deeply why we’re doing what we’re doing (even if it might not work).

As I said above, none of these is strictly wrong, but it wouldn’t be much of a blog post without some strongly worded opinions to polarise the audience. So:

- Waterfall is almost always wrong, unless the requirements are in a contract. In which case you probably failed somewhere in the sales process (a topic for a future blog post). Waterfall deals well with the “known knowns”, but building good software always involves solving problems — product or technical — that we don’t know about on day 1.

- Agile is good, and probably optimal for overall speed and scalability of product development in most cases. Product Managers can focus mostly on the why and what, and Engineers can focus mostly on the how, with some overlap in the middle to find creative solutions. We have the flexibility and whole team collaboration necessary to tackle the “known unknowns” that are key to success.

- Empowered¹ is essential if you want to innovate at the product level: to go from zero to one; to define a new category; or to pursue a deep tech opportunity. Working this way, we can find and tackle the “unknown unknowns”. Disruptive insights come from a strong collaboration between people with different expertise, and Engineering is a key input. But you need Engineers who are willing to stretch into product uncertainty and the world of the customer, and customers who are willing to spend time to partner in a deep way.

Which brings us back to Helsing. We are rethinking assumptions that have been hard-coded into defence technology for decades. Software and AI-enabled products offer new ways to think about customer problems, innovation cycles, and collaboration — we set out to build new defence technology that stands the test of time, but is delivered at the pace of software.

We can’t do that with a Waterfall approach.

We’re starting new products with Empowered teams, involving Engineering and AI deeply in the discovery process to identify new product opportunities. As they become structured and start to be used, we will iterate with our customers in an Agile manner to increase the effectiveness as rapidly and efficiently as possible. When we see a new technical or product opportunity, we’ll switch back to Empowered mode to drive innovation.

Naturally, to make this work, we need to build strong teams of Engineers and AI Researchers who are willing to go the extra mile to maximise their impact. If that sounds like you, please do get in touch.

¹ If you’ve read Marty Cagan and Chris Jones’ Empowered and you’re feeling a little bit of intellectual friction, it’s because I’ve borrowed the word “empowered” and applied it slightly differently. To reconcile the two uses: (a) All teams should be empowered in the sense of the book. Waterfall teams aren’t. Good Agile teams and Empowered teams are — they own the product and are committed to delivering real value, not just features. (b) Teams that are empowered in the sense of the book are — amongst other things — empowered to go deep into customer-land together. The point of this blog post is that this is sometimes critical (zero-to-one, deep tech, product-level innovation), but isn’t needed all the time.