TL;DR: We have built and open-sourced Buffrs , Helsing’s package manager for protocol buffers. In this two-post series, we first explain why we built Buffrs and how it works (in this post), and then provide a step-by-step getting started tutorial in the second post .

Helsing’s software platforms make extensive use of protocol buffers and gRPC to define and implement inter-service APIs. While the open-source protocol buffers ecosystem makes it very easy to get started with a few services and a handful of messages, we have experienced recurring difficulties with scaling gRPC APIs beyond immediate team and repository boundaries for two main reasons: First, there is limited tooling for packaging, publishing, and distributing protocol buffer definitions. Second, there are no widely-adopted best practices for API decomposition and reuse.

To overcome these problems, we have developed and open-sourced Buffrs, Helsing’s package manager for protocol buffers. Using Buffrs, engineers package protocol buffer definitions, publish them to a shared registry, and integrate them seamlessly into their projects using versioned API dependencies and batteries-included build tool integration.

Design goals

The design of Buffrs is motivated by engineering best practices for API design and dependency management, as well as influences from other leading package managers such as Cargo. The following principles have guided the design of Buffrs.

Versioning. A versioning scheme for APIs — similar to versioned library dependencies — explicitly encodes compatibility properties. This allows developers to make either backwards-compatible or breaking changes and encode the compatibility guarantees in the package version: a minor version upgrade “just works”, while a new major version API may require manual migration/adaption in the consuming server/client implementation.

Source compatibility. Given versioned protocol buffers with explicit compatibility guarantees, we strive for a system in which wire-format compatible APIs are also source-code compatible. This means that minor version upgrades can be applied blindly (or in fact automated through tools like Renovate).

Another pitfall with compatibility of generated code are diamond dependencies, which in the worst case make it impossible to combine wire-format compatible APIs due to source-code incompatibility. Moreover, Rust’s orphan rule makes it hard to extend the behaviour of generated code.

Given these considerations, we prefer consumer-side code generation for protocol buffers. A nice side-effect is that different consumers can customise code generation to their respective needs, for example to experiment with different gRPC or transport libraries.

Composition allows developers to reuse and combine code in order to build new systems from existing building blocks. A common composition scheme with protocol buffers is to use a set of base messages and data types across many different APIs. Just like Cargo makes it trivial to write, publish, and consume Crates, we wanted Buffrs to make it easy to maintain and reuse shared libraries of base protocol buffer messages.

Discoverability. Before engineers can reuse and compose protocol buffers, they need to discover and understand what APIs exist and how to use them. Discoverability is a key accelerator for engineering productivity and helps developers stay abreast of the evolution of APIs and architecture. Similar to docs.rs for Crates, we want to maintain a central registry to discover protocol buffer APIs and their documentation and specifications. Further, this registry can assist developers by verifying versioning and compatibility guarantees or generating change logs.

Prior art

Before we started working on Buffrs, we took a look at existing solutions and their strengths and weaknesses. Three common tools are Buf, Bazel, and Git.

Buf. The buf project has pioneered dependency management and tooling for protocol buffers. Unfortunately, we cannot lean on buf at Helsing, because cloud-hosted SaaS solutions are often at odds with the data residency requirements imposed by our customers. In addition, buf distributes compiled language bindings instead of raw protocol buffers; this leads to the source compatibility and flexibility issues sketched above.

Bazel. Google’s build system, Bazel, supports a mature way of depending on third party protocol buffers via proto_library. Bazel takes care of the distribution and local code generation. While Bazel ticks a lot of the boxes we care about, it doesn’t quite fit our needs:

- Bazel’s proto libraries are not explicitly versioned and instead rely on protocol buffers wire format compatibility guarantees.

- Bazel has no registry or other centralised understanding of the APIs and libraries it makes available.

- Bazel is a closed system in which every repository would have to use Bazel, at least as the build system for protocol buffers.

Git. The third common approach is to use Git submodules to distribute protocol buffer specifications across your organisation. This is a good way to get started, but since Git is not meant to be used as a package manager, it reaches its limits quite soon.

For example, Git submodules create a dependency on a particular commit rather than a more flexible version range; this makes API evolution cumbersome and error-prone. Second, monitoring the usage of APIs within large code bases is hard; for example, enumerating downstream users of a given API in order to understand the effect of a deprecation is impossible to answer without significant tooling investment.

Architecture

Buffrs has three main components that support the full development life cycle of protocol buffer APIs:

- The Buffrs CLI supports declaring (

buffrs add), fetching (buffrs install), and publishing (buffrs publish) protocol buffer packages - A Buffrs Registry hosts published protocol buffer packages

- Buffrs provides adapters for local code generators (like

protocortonic) to compile protocol buffers into language-specific bindings

The following diagram shows how those components interact in a typical development flow:

The buffrs add command appends dependencies to the local Buffrs manifest (Proto.toml) that contains package metadata and all (versioned!) dependencies on Buffrs packages. buffrs install fetches the protocol buffers files from the registry and makes them available to the local build system. (More about that in the second blog post!)

Libraries vs APIs

Buffrs encourages engineers to write composable and reusable protocol buffer packages by distinguishing between two types of packages, Libraries and APIs. Library packages are designed for reuse and composition, while API packages primarily define service APIs that are directly implemented by servers and clients. In the previous example, the DegreesCelsius type suits a library package, because it is intended to be used in many different APIs.

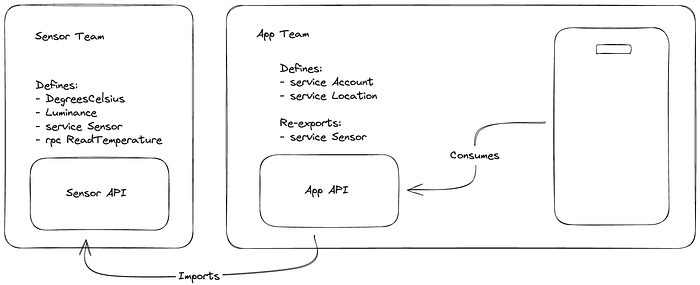

Type reuse in distributed systems APIs is a nuanced problem. We believe that the naïve “re-export” pattern in which other services’ APIs are implicitly redistributed is undesirable as it exacerbates the complexity of systems. Let’s look at a concrete example to understand the problems and how Buffrs can help solve them.

The perils of re-exporting APIs

Say you have two teams, one responsible for maintaining internal services related to sensors (like the Sensor example above), and the other developing a user-facing app that works with such sensors. The app team might decide to simply copy&paste and re-export the SensorAPI from the sensor team in order to stay in sync, since they talk about roughly the same domain concepts (temperature, sensors, etc) and support similar operations.

While this seems like a reasonable engineering decision at first glance, the teams will run into problems as soon as their APIs start to diverge. For example, if the sensor team wants to introduce breaking changes in a new API revision, the app team is forced to immediately adopt the same changes; even worse, they have to ensure that not only the source code stays in sync, but that all deployed instances of their applications and services use compatible Sensor API definitions.

This is of course a simplified scenario, but in an organisation with dozens or hundreds of teams, you will appreciate the amount of technical debt and complexity that this pattern can cause. (And we did not even touch on circular or diamond dependencies…)

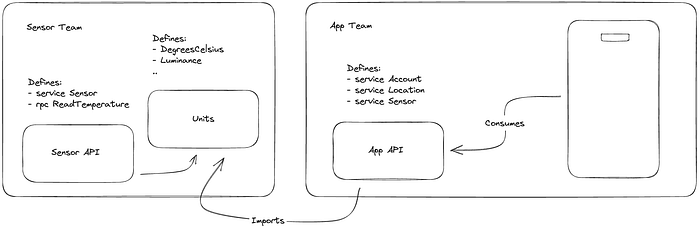

Better decomp with Buffrs libraries

To refactor the above scenario into the mental model of Buffrs, we first split the Sensor API into two packages: a Units library and a Sensor API; the former is designed for organisation-wide reuse and contains simple base types that change rarely or never, for example messages for temperature or luminance measurements.

Then the app team adds a dependency on the Units library and defines their own Sensors service for use within the App API package. This may seem counter-intuitive at first glance (due to duplication of protocol buffers which are very similar if not the same), but solves the problematic dependency of having the App API's compatibility behaviour depending on the sensor team's design decisions. In other words, this is just the common Adapter design pattern.

With this change, every service API definition is now maintained by exactly one team. The shared dependency on the Units library is less problematic since (1) those types are small and simple and don’t change often, and (2) it is straightforward to write adapters for messages if needed. The dependencies are now more explicit and more granular: the App API depends only on those types that it really needs, and not on the entire Sensor API. In the long-run (and in large and complex code bases), narrow and specific dependencies help developers understand and minimise system coupling.

Conclusion

While most programming languages feature a vibrant ecosystem of shared code and libraries (think Rust Crates or PyPI wheels), the protocol buffers ecosystem lacks a distribution mechanism for shared libraries. While we had initially designed Buffrs for our internal use, we believe that the Buffrs project can also help lay the foundations for a trusted open-source package registry for protocol buffers libraries. Of course it’s still early days for Buffrs, but hey, you have to start somewhere :)

The upcoming second blog post in this series will feature a step-by-step tutorial for getting started with Buffrs. Stay tuned! In the mean time, if you would like to use or contribute to Buffrs, please get in touch with us through GitHub pull requests or issues.

Author: MaraS